Zia Mohyeddin: the father, the foodie, the fable

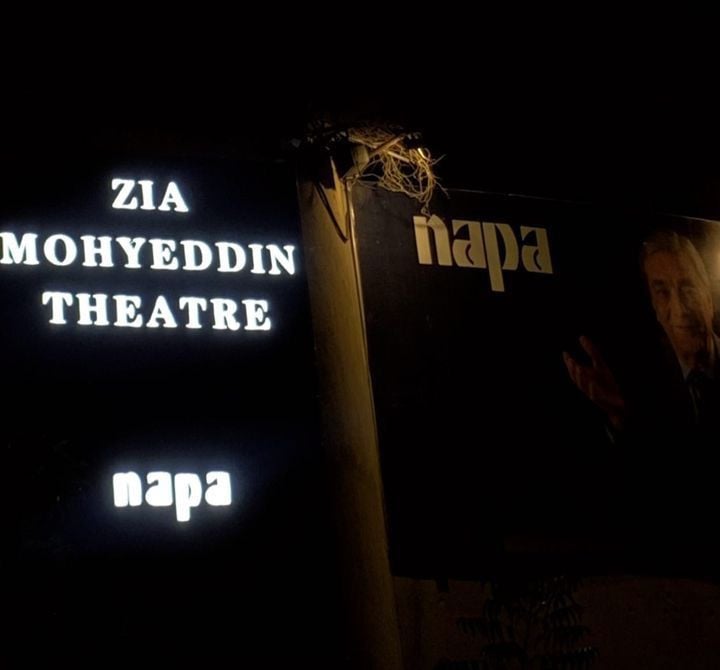

The second day of the Zia Mohyeddin Festival at Napa (National Academy of Performing Arts) was all about remembering the many roles that Mohyeddin lived in his lifetime. There were tears, applause, laughter, silence but most importantly, a clouding sense of grief, so strong, that it enveloped the whole space.

An unexpressive father

Risha Mohyeddin, Zia’s firstborn, looks like an exact clone of his late father. Speaking about his early memories, Risha, a banker by profession, remembered Zia as someone who kept to himself at all times.

“He wasn’t very expressive. He always tried to keep his emotions to himself. People often comment on his attention to detail and his perfectionism, but what they don’t often talk about is how difficult it is to live with a perfectionist,” he paused. “I give credit to Azra for mellowing him out. But I remember I always found it interesting how he had an issue with why other people around him weren’t perfectionists like him. He’d actually get upset over why people are okay with mediocrity and average work,” he laughed.

Whether Zia ever held an expectation for his kids to follow suit in his passion for literature and performing arts, Risha and Aliya both said no. “He had many loves in his lifetime, in many ways you can say, but he didn’t just love literature or arts. Jismai dil lage voh karo (Do whatever your heart pleases), he would say. He walked out of the house when I was 16 or 17 so that may have been a reason too but he never pressured me,” he said.

Risha, who spoke mostly in English during the session, shared how Zia, although never explicitly called him out, had a slight complaint over his son’s command of Urdu. He also expressed gratitude for how close he got to his father in the last few years but didn’t share much from that period.

Aliya Mohyeddin, Zia’s last born with his third wife Azra Mohyeddin, was not just Zia’s only daughter but also his only child that ever got to work in a production directed by the late legend. “One day when he was working on Waiting for Godot, he came home and walked to me and said, ‘I’m looking for a boy,’ and that’s all he said. I said okay, that’s cool, not knowing what he really meant. After a few days, he came to me again and said, ‘You’ll be my boy’ and I was quite surprised but I later learnt that the character in the production was literally called ‘boy,’” she smiled.

Whether she got any special treatment from her father during rehearsals, Aliya straight up said no. “Here, I wasn’t his daughter. I was boy. He treated me like he’d treat boy.” Aliya’s memories of his father are more like an observer than a participant in his life. She recalled how she always just watched him do things in his study or in the living room or elsewhere but barely remembered the conversations they’d have.

“I’d go in his study and listen to him read things. I never asked too many questions. I think I’ve realised how big of a person he was after he passed away. My uncle told me that when I was a kid, some uncle came to me and told me that my father is a legend. I started crying because I thought a legend is a large, scary monster,” she said. “But now I know what a legend he truly was.”

A not-so-demanding husband

Azra shared little moments from the time she spent with Zia to cherish how good of a husband he was to her. “I’d attend his dramas and plays but when I couldn’t, I always asked him how they went. If he said it was fine, then it meant it was amazing. Anyway, I wasn’t there for a few dramas in a row and he came to me and said, ‘Joonum, ap mujhe kuch samjhti hee nahi hain (You don’t think anything of me)” and I laughed. He knew what he meant to me,” she said.

Another story she had was about how he’d always take a step back when stepping outside the house, getting in the car, and entering a hall to make space for her to walk ahead. “His sisters would complain that he doesn’t stop me from doing certain things and he’d come to me and say, ‘Hamsheera was telling me to stop you from something or say something. What am I supposed to do exactly, I don’t understand.’ He never stopped me. We never had arguments about silly patriarchal subjects that our society sees examples of every day. Others have complaints and I am not saying that they aren’t true but I’d just say that when he came into my life, he was a great husband.”

A cultured gentleman

Zehra Nigah, a poet who was close to Mohyeddin, especially while he was filming in London, wanted to shed light on how he was the epitome of mannerism and discipline. “Apart from the fact that he was a great artist, he was a complete gentleman, the most cultured one can be, which is impossible to find in this time, sorry to say. There was no room for you to point out any mistake in his demeanour. From how to walk, stand, eat, and even say goodbye, he was perfect. We would wait for him and notice his actions to point out one thing that he did wrong or inappropriately but no. Never,” her voice echoed.

“There was great respect for language in his world. The man knew four languages; English, Urdu, Persian and Punjabi and mastered all four of them. We don’t have such people left now, do we?” she said adding that he never mixed languages. “He used to speak such English in a way that even the English-speaking world would be amazed. Similarly, with Urdu, his voice would make you feel like he’s painting a scenery where flowers are blooming and leaves are falling. His Persian would sound like poetry to the ears. I never had the chance to hear him speak Punjabi but he used to talk to Faiz Ahmed Faiz in Punjabi a lot.”

The poet emphasised that if there was one thing that Mohyeddin couldn’t tolerate, it was the disrespect of language. Sharing an anecdote about how he valued preparation, passion and honesty when it came to adab, she added, “This one time, my daughter-in-law and I were reading Sylvia Plath’s poem Lady Lazarus, it’s a very difficult poem to analyse and understand and we were stuck with a few verses. During that time, Zia was staying with us in London and so she said, ‘Let’s wait till evening. We’ll ask Zia bhai to comprehend it for us.’”

He came back home and asked for more time to get back to them. “‘Zia bhai, if you’d read this poem on stage, would you ask for more time? You’d have read it anyway,’ my daughter-in-law said and that’s where Zia stopped him. ‘I would’ve stopped on stage and definitely asked for more time. I have never read anything on stage without understanding it.’ Zia said,” Zehra quoted while sharing a couplet that fit the orator’s perfectionist persona.

Uski mehfil ki dekhna tehzeeb

Baat ka ehtamam hota hai

“The beauty of performing that Zia was blessed with is incomparable. That void will forever remain hollow but it is my prayer that one of his students here will breathe life into his passion and keep it alive,” she concluded.

A foodie through and through

Anyone who spent time with Zia knew that his tastebuds weren’t easy to please. His wife Azra shared that Zia was never a simple “daal roti salan” but wanted proper feasts for dinner and she made sure to keep it like that too. “This one time I even made a video of how he’d like 5-6 dishes on the dinner table all set in a fancy manner but he’d take merely a bite from each,” she recalled.

Upon food anecdotes, everyone in the panel had a story to tell. His nephew, chuckling, shared that he once called the chef and told him how “talented” he really is for making food so bad is a skill on its own. Risha, his son, also shared how they were guests at someone’s place in Birmingham and at the dinner table, Zia said, “‘Wow! I’ve never had such kebabs before.’ but when we got in the car, he complained about how terrible the kebabs were. When I confronted him on how he said something else in their house, he said, ‘I didn’t lie. I’ve never had such bad kebabs ever in my life.’”

Gul Jaffri, sister of Azra, also shared how good of a cook Zia was. “I once made Kofte when he was visiting us in Singapore. The next morning, he was up before everyone else and he made Kofte again because he didn’t like mine,” she said adding that while she was a bit hurt at that time, it was these peculiarities about food that added colour to Zia’s life.

A pioneer in life

Culture curator Sharif Awan couldn’t find words to describe his relationship with Zia. Expanding on Zehra’s comment on Zia’s love for music and language, he shared that “Urdu was a language to be read, written, and spoken but the recitation of it, the idea of listening to Urdu came after Zia,” he said and many related to the sentiment. “I can guarantee that even if you listen to a reading by Zia Sahab, it will leave a different feeling in your heart every time. This ‘ras’ that was in his music is a principle of classical music and rhythm.”

Munawwar Siddiqui, who has known Zia sahab for over 60 years, and has worked with him in theatre, film and TV, shared how Zia convinced Khwaja Moinuddin to make the first drama with an actual set instead of a screen with drawings on it. “We were working on Lal Qile se Lalukhet Tak and he walked up to Khawaja sahab and said I want to direct your play and I want to do it with a full set and that was a bizarre thing to say at that time because we never shot with sets but Zia made it happen. At that time, we spent months together.”

Upon why the film industry lost Zia, Munawwar lamented the delayed time schedules. “If the call time is 10 am, then Zia would be ready at 9:45 and be on set. However, other people would not even wake up before 12 and he couldn’t work with that. He tried to change it in many ways but eventually realised that the change wasn’t coming,” he said sadly.

Leave a Reply